An hour before a cloudless September sunset, Kyle and I pitched our tents at the Ash River Campground and waited for his brother, Braden, so we could begin our five-day, father-son adventure at Voyageurs National Park. A Minnesota DNR pocket park across a gravel road from its eponymous waterway, you self-register for the eight first-come, first-serve sites. Three bucks short of the $14 fee, we hoped Braden had $3, so we wouldn’t have to sacrifice a $20.

NOAA weather radio warned of coming rain. Pitched on Site 8’s level spots, our tents formed an obtuse triangle with two trees suitably spaced for Braden’s hammock. A 28-year old mechanical engineer, Kyle traveled from St. Louis to join me in Omro. Braden, a 31-year-old ICU nurse, was on his way from Kansas City, where he’d settled with his family after five years with the Navy.

When Kyle wandered into the gloaming in search of a cell signal, I slouched on the picnic table and stared at the celestial hi-def big screen framed by the surrounding trees. A loon warbled in the deepening darkness and the Milky Way came into focus. I’d last seen the Milky Way in 2006, the year Braden graduated from high school. We three were camping in the wilds of south-central Missouri to raft our way down the Niangua River.

When Kyle wandered into the gloaming in search of a cell signal, I slouched on the picnic table and stared at the celestial hi-def big screen framed by the surrounding trees. A loon warbled in the deepening darkness and the Milky Way came into focus. I’d last seen the Milky Way in 2006, the year Braden graduated from high school. We three were camping in the wilds of south-central Missouri to raft our way down the Niangua River.

That was the last adventure until now. We made our first big trip in 2002, a five-day guided tour of the Apostle Islands that introduced us to sea kayaks and Lake Superior. We saw the Milky Way there, too.

Annual adventures seemed the best way for me, a noncustodial father, to spend time with my sons that built lasting memories. They sustained us through their college years and the inauguration of their careers. We gathered at Braden’s new home for Thanksgiving 2017. Marking the commencement of my 64th year the next day, we recalled the highlights of our adventures, and we immediately agreed that it was time to resume them.

Since we had the boats, it must be a kayak adventure. I’d built an 18-foot CLC Chesapeake the year after the Apostle trip, and Kyle would paddle the 17-footer I built for my wife several years ago. Braden has a 17.5-foot Pygmy Coho Hi that he built while stationed at the Camp Jejune Marine Base Hospital in North Carolina.

Since we had the boats, it must be a kayak adventure. I’d built an 18-foot CLC Chesapeake the year after the Apostle trip, and Kyle would paddle the 17-footer I built for my wife several years ago. Braden has a 17.5-foot Pygmy Coho Hi that he built while stationed at the Camp Jejune Marine Base Hospital in North Carolina.

We considered an Apostles redux but then came to our senses. With wetsuit water temps and robust reactions to weather, prudent, inexperienced Lake Superior paddlers opt for experienced guidance. This adventure had to be DIY, flexible, and affordable. But where? Braden remembered his Eagle Scout trip to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, and then he remembered all the portages. Sea kayaks don’t portage well.

Recalling a seminar at Canoecopia, Madison’s annual paddling extravaganza, I suggested Voyageurs National Park. Snuggled against the Canadian border between Ely and International Falls, the speaker said it was like the Boundary Waters without portaging, and a boat is the only way to reach campsites scattered among its roughly 500 islands.

Wanting to avoid bugs and people, we committed to September 2018, after Labor Day. Appointed plan master, my research was now becoming reality. Stumbling into a dark ditch on his way back to camp, Kyle cursed. He reported a no-bar cell signal, but he did somehow get a Snap Chat from his girlfriend.

Staring at the stars, we hoped that Braden would have $3. He arrived at 2115 and reached for his wallet. As he hung his hammock, the clouds steadily thickened like new sponges tossed into a star-filled pond. Mother Nature waited until sleep found us before squeezing the rain out of them.

Planning & Preparation

By Google results, Voyagers National Park is not very popular with kayakers. Fishermen and house boaters, yes. Paddlers? Not so much. The only thing close to a current guidebook I found was Steve Parrish’s 2015 report at Central Iowa Paddlers. But it got me started; that’s how we ended up at the Ash River Campground.

Looking at the park’s website map, most of Voyageurs National Park’s 218,200 acres are covered by interconnected lakes, Rainy, Kabetogama, Namakan, Sand Point, and Crane. Three visitors centers are the primary access points. The Rainy Lake center, 12 miles east of International Falls, anchors the park’s western border, and the Crane Lake Ranger Station is the eastern portal.

Looking at the park’s website map, most of Voyageurs National Park’s 218,200 acres are covered by interconnected lakes, Rainy, Kabetogama, Namakan, Sand Point, and Crane. Three visitors centers are the primary access points. The Rainy Lake center, 12 miles east of International Falls, anchors the park’s western border, and the Crane Lake Ranger Station is the eastern portal.

On the park’s south side are two seasonal centers, staffed by volunteers from late May through late September. Situated in the middle of the lake’s southern shore is the Kabetogama center. To the east, in the narrow passage that leads to Namakan Lake, is the Ash River center. It was our logical starting point. From there we could paddle to either lake. With the campsite map showing a surfeit of nearby islands, we would paddle east into Namakan.

Looking at my thumbprint-smudged monitor, I needed a better way to measure the distance between the island campsites. The measurement tool on BaseCamp, Garmin’s PC planner, would work if I had TOPO 24K maps that depict terrain details at 1:24,000 scale and include searchable points of interest, including campsites. My old handheld GPS couldn’t swallow the map’s microSD card, so I rationally replaced it with a waterproof Garmin eTrex Touch 35t, which came with a 100K topographic base map, compass, and barometric altimeter.

A Fox River paddle dashed my hopes that the new GPS’s turn-by-turn road and trail directions would extend to waterways. With the GPS needle pointing directly at our destination, when an island was in our way we’d have to figure the turns on a map. National Geographic’s Trails Illustrated Topographic Map on waterproof, tear-resistant paper depicts topographic details and identifies all of VNP’s navigation buoys and campsites.

Our Namakan adventure would be a pinball paddle. Focusing on our daily distances, I should have paid more attention to each campsite’s amenities before selecting our destinations. Every island site has a privy, picnic table, critter-proof food locker, tent pads, and fire ring. After plotting our route, I visited the photo gallery of the Namakan Lake campsites. These included an important, specific amenity—the landing. Three of my first four choices had docks, invitations for getting wet when getting in or out of a kayak.

Our Namakan adventure would be a pinball paddle. Focusing on our daily distances, I should have paid more attention to each campsite’s amenities before selecting our destinations. Every island site has a privy, picnic table, critter-proof food locker, tent pads, and fire ring. After plotting our route, I visited the photo gallery of the Namakan Lake campsites. These included an important, specific amenity—the landing. Three of my first four choices had docks, invitations for getting wet when getting in or out of a kayak.

Starting over, I went a step further and identified all of the sand or pebble beach landings on my NatGeo map. Besides simplifying my redo, it gave me one-glance peace of mind should we need rapid refuge from wet and sparkly weather. Next, I downloaded and similarly edited the list of campsite GPS waypoints.

When shoreline property today is private, Voyageurs National Park is as close as we can get to exploring a watery wilderness as the park’s namesakes once did. Claiming campsite is not first-come, first-served. With a $10 fee, you must reserve each one at recreation.gov for $20 a night. A coded calendar shows the availability of each one. With a few clicks, a credit card, and some related information, you’re done after reading and accepting VNP’s rules and regs.

Emails confirmed our campsite reservation. Printing the Visitor’s Permit limits the refund options. After consulting the long-term forecast, which suggested several days with increased chances for rain and temperatures in the seasonal ballpark, lows in the 40s and highs in the 60s, I clicked “Print” four days before our registered start.

Emails confirmed our campsite reservation. Printing the Visitor’s Permit limits the refund options. After consulting the long-term forecast, which suggested several days with increased chances for rain and temperatures in the seasonal ballpark, lows in the 40s and highs in the 60s, I clicked “Print” four days before our registered start.

In an email confirming our adventure, I sent a float plan for the boys to share with their mates. It said when and where we planned to be and included identifying details, such as our ages and the colors of our boats and PFDs. Numbers to call for search parties if we didn’t communicate by our expected return to cell service followed.

We promised to try daily check-ins, but we repeated the park’s website warning of limited or no cell service. Finally, we proved our preparedness with a list: VHF marine band radios (the park monitors emergency channel 16), signal mirrors and flashing headlamps, first-aid kits, fire starting materials, water filters, and week’s food for a four-night trip.

Getting Underway

With no-bar signals, we turned off our phones to save the batteries. I forgot my weather-station carabineer watch, and Kyle’s $11 “wonder watch” didn’t have an alarm, so our circadian rhythms would dictate our days. Up first, thanks to my bladder, I enjoyed a beaker of hot Starbucks Via on a cool misty morning. Kyle’s tent snored and Braden was a silent hammock sausage. Halfway through my second coffee, the boys stirred.

Nosing to a stop at the Ash River Visitors Center, rainwater sloshed in the kayak cockpits. Climbing the stairs to the rustic brown structure, I had to duck through the doorway of what once was Meadwood Lodge. The anteroom displayed books, souvenirs, and a rack of National Geographic maps. In the next room, its walls covered with storyboards of park history, a tidy fire crackled in the fireplace.

Nosing to a stop at the Ash River Visitors Center, rainwater sloshed in the kayak cockpits. Climbing the stairs to the rustic brown structure, I had to duck through the doorway of what once was Meadwood Lodge. The anteroom displayed books, souvenirs, and a rack of National Geographic maps. In the next room, its walls covered with storyboards of park history, a tidy fire crackled in the fireplace.

At the cash counter, a volunteer said there was no check in, “Just hang your Visitor’s Permit on the bear box.” The permit was a Trip Itinerary that listed how many people could stay at the reserved site on the given day. “Mon Sep 10 2018-Tue Sept 11 2018 (1 Night) Namakan Island South-N63 Group Size: 3.”

Boat ramps with parking lots bookend the visitor center; to the east is a concrete incline for powerboats, and to the west, we portaged our boats (after dumping their collected rainwater) down a tree-lined trail to a low dock and narrow pebble beach. Then we began the dry-bag shuttle run.

Having practiced a load out in Omro, Kyle and I finished first. Braden moved a small mountain of small dry bags that he fed into the open deck hatches like a momma bird. As we geared up, he unsuccessfully searched for his spray skirt, which covers the gap between his torso and cockpit coaming. If the weather behaved, he’d stay dry.

Having practiced a load out in Omro, Kyle and I finished first. Braden moved a small mountain of small dry bags that he fed into the open deck hatches like a momma bird. As we geared up, he unsuccessfully searched for his spray skirt, which covers the gap between his torso and cockpit coaming. If the weather behaved, he’d stay dry.

BaseCamp measured our first leg at 6 miles. At 1130 GPS time, we paddled on calm water for Namakan Island. Rounding Portage Beach, we aimed for the green dot on the watery horizon, Buoy C29 according to the map. Passing it, we banked southeast toward the next green dot, Buoy C27.

Going two-for-two calmed my navigation anxiety. Crossing the mouth of Old Dutch Bay, we turned northward toward Red Buoy 26, past Ziski Island on the left, and on to Green Buoy 23 and Blind Indian Narrows. Threading our way between Sweetnose Island and an unnamed hump of trees, we passed Red Buoy 22 and beached at Cemetery Island for lunch.

Knuckles deep in the trail mix bag we watched a bald eagle wing and wheel, searching for its lunch. We’d seen maybe a dozen eagles so far, and we wanted to see at least one catch its meal. Braden, who’d bought a Minnesota fishing license, followed suit as we paddled on. After sprinting ahead he’d cast away while we caught up. His luck was no better than the eagle’s.

Knuckles deep in the trail mix bag we watched a bald eagle wing and wheel, searching for its lunch. We’d seen maybe a dozen eagles so far, and we wanted to see at least one catch its meal. Braden, who’d bought a Minnesota fishing license, followed suit as we paddled on. After sprinting ahead he’d cast away while we caught up. His luck was no better than the eagle’s.

Just off Sexton Island, we rounded Red Buoy 20. Passing Stevens Island, the GPS pointed unobstructed at Namakan Island Campsite N63. We skidded into the sand beach at 1410. After sitting for so long, my unsteady exit landed me butt first in the water, earning a giggly round of applause. The GPS reported a 6.2-mile paddle in two hours, with a total trip time of more than 2.5 hours. I didn’t think lunch lasted that long.

With the sun growing warmer through the dissipating clouds, we hung our tents to dry before pitching them. While sitting at the shoreline, pumping water through my filter, Kyle muttered “shit!” Anxious to use his new Steripen UV water purifier…he’d forgotten batteries. Muttering, he handed me his water bottle and wandered inland to explore.

With the sun growing warmer through the dissipating clouds, we hung our tents to dry before pitching them. While sitting at the shoreline, pumping water through my filter, Kyle muttered “shit!” Anxious to use his new Steripen UV water purifier…he’d forgotten batteries. Muttering, he handed me his water bottle and wandered inland to explore.

While gravity pulled water through the filter between his water bags, Braden worked his fishing pole. He shortly had words with an aggressive northern pike that stole his lure and leader. Replacing them, he caught the same fish again, the pilfered tackle dangling from its mouth. This time he got it on the bank, but it flopped back to the lake before he could mete out justice.

Our tent pads were maybe 12-feet square, outlined with stacked timbers. Filled with sand, they were level, lump free, and well drained. Braden took up residence in the trees behind Kyle’s tent. There was enough room in the boys’s bear box for all their dry bags, including Braden’s fifth of Jamison’s and 12-pack of Coke cans. Where does he put all of this stuff in his boat?

Made of diamond steel mesh covered in brown vinyl, the picnic table’s benches are cheese grater comfortable. I didn’t immediately notice this because I was listening to the water softly purl the pebbled beach like a lazy cat lapping milk. Muted by distance, an outboard motor humbuzzzed. We’d seen one distant houseboat and a few anglers; those who passed closely respected of our paddle-powered craft.

Made of diamond steel mesh covered in brown vinyl, the picnic table’s benches are cheese grater comfortable. I didn’t immediately notice this because I was listening to the water softly purl the pebbled beach like a lazy cat lapping milk. Muted by distance, an outboard motor humbuzzzed. We’d seen one distant houseboat and a few anglers; those who passed closely respected of our paddle-powered craft.

Kyle emerged from the woods bearing an armload of fallen deadwood. The frustrated fish fighter followed him back into the woods. As Eagle Scouts, they came prepared for campfires. Braden packed a folding saw and Kyle bought a big knife for shaving kindling. Instead of using some of his stove’s white gas, Braden got things started with Vaseline soaked cotton ball.

Kyle ate commercial camp meals. Braden and I made our own dehydrated delights. Because I didn’t want to pack out the leftovers, I ate on oversized portion of zippy spaghetti. I might have been okay if Braden hadn’t brought appetizers, addictively delicious bags of backstrap deer jerky and dried kiwi.

Kyle ate commercial camp meals. Braden and I made our own dehydrated delights. Because I didn’t want to pack out the leftovers, I ate on oversized portion of zippy spaghetti. I might have been okay if Braden hadn’t brought appetizers, addictively delicious bags of backstrap deer jerky and dried kiwi.

With the fire crackling into a cloud free sky, we quietly probed the Milky Way. We hoped the weather would hold because Braden said the forecast predicted their first sight of the northern lights for Thursday

Wind & Waves

Before opening my eyes, I listened to the morning sounds. Fish splashed and distant anglers buzzed softly to their secret spots. Chirps and peeps surrounded me and an undecipherable fluttering rustled the leaves next to my tent. What kind of critter was playing with my imagination?

Motivated by micturition, I crawled out and saw the sound. Smaller than my clenched fist, a short-winged brown bird darted in and out of the shrubbery. Above it, the trees were dancing in a brisk breeze under a cloudless sunny sky. Without a spray skirt, today was going to suck for Braden.

With a south wind blowing 15 mph, at 1123 we nosed into a 12-inch chop and turned eastward for Pike Bay and Campsite N31. Braden yelped with bigger cold lap splashes and periodically sponged his cockpit dry. With the boats wanting to weathervane, we clawed our way east with slow, asymmetric strokes. We beached on the lee side of McManus Island for lunch. The GPS said we’d covered 2.2 miles in 2.5 hours, an average of .9 mph.

This was Kyle’s fault. Yesterday he’d boasted that his first paddle since 2002 had been too easy. He didn’t think so during lunch. It was going to be long 6-mile day. As we pushed off the beach, Braden assured himself that he’d never again forget his spray skirt.

This was Kyle’s fault. Yesterday he’d boasted that his first paddle since 2002 had been too easy. He didn’t think so during lunch. It was going to be long 6-mile day. As we pushed off the beach, Braden assured himself that he’d never again forget his spray skirt.

Paddling through the channel between McManus and Sheen islands, we crawled along the south sides of the Wolf Pack, Fox, and Jug islands and clawed our way past Randolph Bay and Smugglers Point. With the wind, we were within spitting distance of the Canadian border.

We rounded the point that forms Pike Bay around 1400 and found placid water gently massaging a wide sand beach. Flopping out of our cockpits, we rested on sun-warmed sand caressed by a whispering wind. A weightlifter, Kyle worried that our asymmetric marathon might have made his right trapezoid larger than his left. I was wondering if my supply of cigars and Tullamore DEW would allow a twofer, one now, and another with our campfire.

While Kyle napped on the sand, I waded into Pike Bay for a bath and Braden went to hang his hammock. In the middle of my refreshing soap-free scrub, Braden slid back into his boat with his fishing pole. “I forgot my tree straps,” he grumped. He improvised a paracord replacement, and I said we could stop for them on our way back the day after tomorrow.

While Kyle napped on the sand, I waded into Pike Bay for a bath and Braden went to hang his hammock. In the middle of my refreshing soap-free scrub, Braden slid back into his boat with his fishing pole. “I forgot my tree straps,” he grumped. He improvised a paracord replacement, and I said we could stop for them on our way back the day after tomorrow.

“If I can’t catch a fish in 20 casts, there are no fish here,” Braden said as he drove into the beach. Roused by Braden’s return, Kyle waded in for a bay bath, then joined him for a firewood forage. Facing northeast, trees blocked our sunset view, but the Milky Way was majestic. Was this a good omen for Thursday’s aurora borealis? Either way, I gave silent thanks for this opportunity to know the men my sons had become.

Spanglers are an unpretentious lot, and tact is a recessive gene, so our unfiltered communication has always been clear and concise. They dismissed my worries about being a noncustodial father. Never did they feel abandoned or ignored. “You were always honest, open, and straightforward,” said Kyle. No one had to guess where anyone stood, said Braden, who is employing this himself as the father of a blended family of four boys.

Spanglers are an unpretentious lot, and tact is a recessive gene, so our unfiltered communication has always been clear and concise. They dismissed my worries about being a noncustodial father. Never did they feel abandoned or ignored. “You were always honest, open, and straightforward,” said Kyle. No one had to guess where anyone stood, said Braden, who is employing this himself as the father of a blended family of four boys.

Kyle parroted my tattoo warning when they were in high school: “If you come home with ink, I’ll remove it with a belt sander.” Nodding agreement, I asked his point. “You also said that when we turned 18, we could make—and be responsible for—our decisions.” The only thing I’d ever said about his shoulder and half sleeve were my compliments to the artist and questions about the meanings of the Japanese-inspired scenes.

Our conversation faded as the fire became slumbering embers and the trees started to dance in the wind. NOAA Weather radio said storms were in the offing.

Rain & Recovery

We awoke early to overcast skies, a decreasing breeze, and a good forecast: partly sunny, 70 degrees, a light breeze, and a small chance of scattered showers. We breakfasted, broke camp, and paddled away from our nicest campsite of the trip at 0955.

We awoke early to overcast skies, a decreasing breeze, and a good forecast: partly sunny, 70 degrees, a light breeze, and a small chance of scattered showers. We breakfasted, broke camp, and paddled away from our nicest campsite of the trip at 0955.

An easy 5-mile paddle to Junction Bay and Campsite N14 revealed a green-season navigation challenge. It is nearly impossible to tell where one forested island ends and the one behind it begins. Instead of the shorter route to the south, that’s why we paddled the long way around Wolf Pack Islands, which looked like they were connected to Sheen Point.

The map showed a gap between Sheen Point and McManus Island. All we saw was a shoulder-to-shoulder line of trees standing behind an unbroken screen of reeds. With our early start and a sunshine sky, we’d have plenty of time to take the long way round, if needed. We didn’t need. There was a gap in the reeds one kayak wide.

The map showed a gap between Sheen Point and McManus Island. All we saw was a shoulder-to-shoulder line of trees standing behind an unbroken screen of reeds. With our early start and a sunshine sky, we’d have plenty of time to take the long way round, if needed. We didn’t need. There was a gap in the reeds one kayak wide.

Confusion reigned when the GPS pointed at a rocky point topped by small brown sign for Campsite N14. Where was the beach? Rounding the knobby point, Kyle warned me about a submerged rock just before I went aground. Not 15 feet ahead of me, rustic stairs climbed the hill from a narrow pebble beach. It took me a few minutes to skootch myself off the rock, and the boys enjoyed the show from shore. I joined them just before noon.

During lunch, I looked at the map, checked the GPS, pointed at Namakan Island, and told Braden that his tree straps were 2.6-miles thataway. Kyle said he’d go with him. Suffering from a poor night’s sleep and with the sniffles working on my sinuses, I promised to keep an eye on camp.

Before they launched, Braden found his spray skirt. Showing off his PFD, he explained every strap and pocket. When I asked what was in a right-side pocket, he said “nothing.” It didn’t look it, so I tugged the zipper and freed a wadded ball of fabric. Without a word, he gave me a hug.

Radio equipped and following the GPS, the boys paddled away under sunny skies. As they diminished in size, the trip’s first mosquitoes buzzed into camp. Then saturated clouds slid overhead, and I strung up my 10-foot tarp over the picnic table before they dripped on me.

Returning with Braden’s tree straps, they said they didn’t see any rain, or campers. By the map, we’d passed many campsites, but they are so discrete that we only saw one, a group site with tents and tarps. The campers must have been fishing because the dock was boatless.

Returning with Braden’s tree straps, they said they didn’t see any rain, or campers. By the map, we’d passed many campsites, but they are so discrete that we only saw one, a group site with tents and tarps. The campers must have been fishing because the dock was boatless.

Shortly after their return, a 15 mph south wind whipped whitecaps into the water. We hauled the boats off the beach before the approaching thunderstorm further churned the water and then took refuge under the tarp. Braden and I padded the cheese grater bench with dry bags. Kyle sat on his weightlifter-thick glutes.

Reaching into his Harry Potter dry bag, Braden pulled out Ziplocs full of deer jerky and kiwi. There was little left after the storm blew through giving our campsite an excellent Wednesday sunset view. As our campfire replaced the sun, we shared hope for a cloudless stage for Thursday’s northern lights.

Clouds & Congestion

We had a short, quick paddle to Campsite N44, Williams Island South. Heading west, the wind increased past Postage Island, but the weathervane worked for us as we followed the shoreline until Williams Island stood before us. We covered the 3.8 miles in 1.3 hours, arriving on another narrow pebble beach at 1040.

We had a short, quick paddle to Campsite N44, Williams Island South. Heading west, the wind increased past Postage Island, but the weathervane worked for us as we followed the shoreline until Williams Island stood before us. We covered the 3.8 miles in 1.3 hours, arriving on another narrow pebble beach at 1040.

My sniffles had matured, so I took a nap while the boys foraged for firewood. Unsure if sleep found me, I felt better when I crawled out of my tent on sore shoulders. I massaged them with memory’s balm of gently bobbing with my boys on the lee side of an island, watching eagles look for lunch. If we see the aurora borealis tonight, the only fantasy so far unfilled is seeing an eagle snag its supper from the lake.

Braden had better luck than the eagles; he caught a small mouth bass. Trying for a second, he changed lures and snagged a northern pike. With Braden’s short pole, Kyle had no such luck. From his magic dry bags, Braden withdrew fillet knife, breading, and cooking oil and prepared a delicious appetizer.

Braden had better luck than the eagles; he caught a small mouth bass. Trying for a second, he changed lures and snagged a northern pike. With Braden’s short pole, Kyle had no such luck. From his magic dry bags, Braden withdrew fillet knife, breading, and cooking oil and prepared a delicious appetizer.

The clouds started moving in after dinner. While Kyle was preparing to light the evening’s entertainment, two loons paddled silently by in water behind him. With a tufted gray comforter of clouds hiding any glimmer of the northern lights, I turned in early.

Dead Man Paddling

Our safe return to the Visitors Center is proof that VNP is a benign but worthwhile DIY adventure. Its forested confines moderate Mother Nature’s moods, the campsites are excellent, and at no point did we get unintentionally wet. This allowed me, with my cold near its turgid redline, to paddle on pure muscle memory. We launched at 0800. Braden and Kyle led the way and set an endurable pace that covered 5.3 miles in about 2 hours.

Rather than shuttle-run our gear to the parking lot, the boys toted the loaded boats up the path. On the road, just before Braden’s exit for Kansas City, we stopped in Virginia, Minnesota, for lunch at Adventures Restaurant and Pub. Spending time again under the Milky Way was good, we agreed. But we still wanted to see the northern lights. Returning was our only logical solution. Besides, there was so much more to explore.

Flying two passengers, they had $6, $4 for red 80-octane avgas and $2 for dinner. Bach didn’t describe his path into town, but he said it was about a mile from the airport. On the way, they passed Al’s Sinclair, and they saw an A&W Root Beer stand not from it. The airport hasn’t moved since the Rio Flying Club built it 1959, so they must have walked south on Highway 16, then east on Rio St. to Lincoln Ave. There was no sign of Al’s Sinclair or A&W, but the business district is still two blocks long.

Flying two passengers, they had $6, $4 for red 80-octane avgas and $2 for dinner. Bach didn’t describe his path into town, but he said it was about a mile from the airport. On the way, they passed Al’s Sinclair, and they saw an A&W Root Beer stand not from it. The airport hasn’t moved since the Rio Flying Club built it 1959, so they must have walked south on Highway 16, then east on Rio St. to Lincoln Ave. There was no sign of Al’s Sinclair or A&W, but the business district is still two blocks long. As it often does in many small towns, one compelling building summarizes history and progress, such as it is. In Rio, it was the Econowash. Above the door, the stone lintel proclaimed the entrance to First National Bank. Without a washer or dryer for folding table in sight through the dirty, smudged windows, it was clear that it ceased to be an Econowash some time ago. Standing back to get a better angle on the second floor windows, those rooms seemed equally empty.

As it often does in many small towns, one compelling building summarizes history and progress, such as it is. In Rio, it was the Econowash. Above the door, the stone lintel proclaimed the entrance to First National Bank. Without a washer or dryer for folding table in sight through the dirty, smudged windows, it was clear that it ceased to be an Econowash some time ago. Standing back to get a better angle on the second floor windows, those rooms seemed equally empty.

Amiot’s website

Amiot’s website

Passing through Canada’s towns and villages is important because serendiculous sights and encounters demand further examination. Each of them is potentially rich with opportunities to overcome our virtual social media isolation with literal face-to-face interactions. It is an excellent way to meet and get to know our long-time neighbor, another reason for this journey. (Do you know the names of your next door neighbors? How about their last name? And when was the last time you talked with them?)

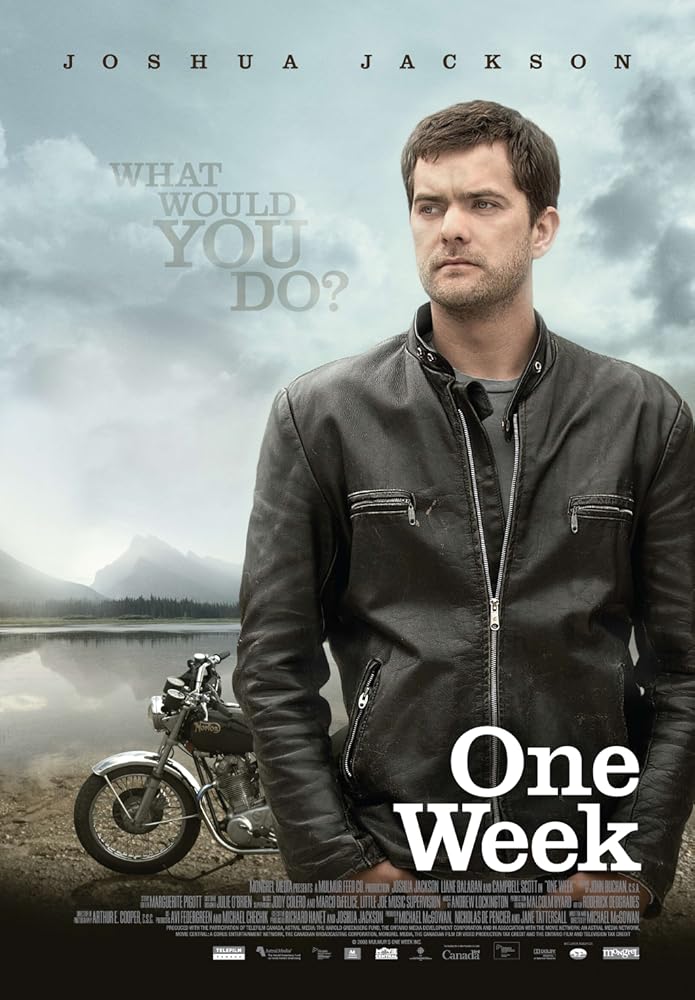

Passing through Canada’s towns and villages is important because serendiculous sights and encounters demand further examination. Each of them is potentially rich with opportunities to overcome our virtual social media isolation with literal face-to-face interactions. It is an excellent way to meet and get to know our long-time neighbor, another reason for this journey. (Do you know the names of your next door neighbors? How about their last name? And when was the last time you talked with them?)  Instead of immediately pursuing treatment he postpones his impending wedding, buys a motorcycle, a Norton Commando, and sets out on a journey from Toronto to Tofino, an island that is the western terminus of the TransCanada Highway. His goal? To make memories that give what’s left of his life value beyond its prosaic routine.

Instead of immediately pursuing treatment he postpones his impending wedding, buys a motorcycle, a Norton Commando, and sets out on a journey from Toronto to Tofino, an island that is the western terminus of the TransCanada Highway. His goal? To make memories that give what’s left of his life value beyond its prosaic routine.